Stream One of the Boys on these platforms:

This is a work of fiction. Aside from the photographs of the models, all the names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this website are either the product of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Though Noah just turned 19, he learned how to drive when he was 12. He was born into a family of farmers in Sagada - past the swooping plateaus and spectral terrains that make up the Mountain Province. His mother (if you could still call her that) was the sole heir to a booming business in Pasay. She fell in and out of love with Noah’s father in one summer, just enough for her to get pregnant and drop out of school for a year. She gave birth in Sagada, in the middle of Typhoon Caloy, to the hands of a mid-wife who would eventually be the one to drop Noah off to his father when his mother left two days after.

His father called him Noah for the storm. And he hasn’t not been a storm since.

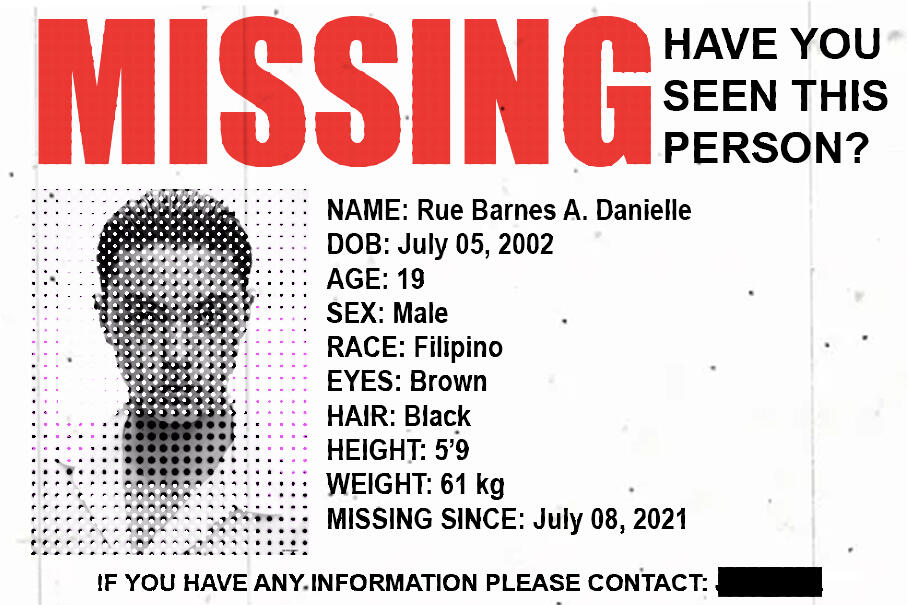

Void of parental supervision at a young age, Noah had to venture off into the world autonomously. This caused him to be reckless with his actions - picking up smoking, drinking, and gambling habits at a young age and running off with friends for days on end. One time, his father and their neighbors conducted a search mission for him after he had abandoned their home for two weeks. This was the incident, among others, that got him sent to his aunt’s all the way down in Metro Manila, given unbreakable instruction that he be monitored. Despite this, he still ran amok. But city life was a much different feat compared to the province. Here Noah learned not only how to keep his bad habits, but also how to make them into something so much bigger than him.

To his and everyone’s surprise, Noah was good with his words.

His writing gave him a new sense of purpose. Yes, he still did all the bad things he was known for in the province, but a switch in him had undeniably flicked. When he acquired (stole, to be precise) his first Moleskin and realized the power he held with his pen, he decided to use it for good. And though he wasn’t known for this skill - at least not as well as he is known for his straight face in poker - he knew this was the only crime he was ever willing to serve time for.

Valentino’s parents knew he was handsome before he was born. His parents, young and drunk they had been when they had him, were children of dermatologists. They would soon become heirs of separate cosmetics business and, to ensure a silver spoon for their child, establish a third, joint venture that proved more than successful.

It was this vanity that made Valentino loathe his parents.

Bestowed the name of a dying haute couture company, Valentino Rojo was meant to roll off the tongue and pose in front of the camera instantly. Not only was he lucky in the looks lottery, he was also a good singer, dancer, model, actor, and athlete. His parents, having seen his potential in everything, kicked him around like a soccer ball. He had earned his first salary at five years old, after attaining a gig in a popular Filipino television series — his first ever move in his never-ending career. He had all the traits needed to grow a fandom. But before he grew up to be the chick magnet he’d be known as, he endured years and years of swimming lessons because his parents said (and this quote is straight from YES! Magazine) “he has the chops for an Olympic medal.” After having gained notability as an actor, he jumped right into The Voice Kids when he was nine years old, falling just short of the champion title.

On the car ride home, Valentino had not cried. His parents did. They bawled and they wept just enough to make him feel like he had failed them immensely.

His supporting role in a blockbuster comedy film landed him a multi-million network contract at age 15. This was when things took a sharp turn. In secret, Valentino declined the offer, enraging his parents. Efforts to speak to them properly were futile. All of a sudden, they had contacted lawyers from all around the country in hopes they could strike a conservatorship for the child. Valentino retaliated and leaked this information to the press and urged them to take action through a short memoir on his blog. This caused a media frenzy with Valentino’s loyal fans, boycotting products from all three of the family’s business endeavors and sparking protests in branches nationwide. The furthest it had gone was when a fan had slashed his parents’ tire while driving which almost sent them flying off the overpass in Mabini.

Valentino’s parents took no legal advice when cutting off ties with their son.

Having moved out to a separate apartment (still paid by his parents) at 17, Valentino struck a book deal to extend the now viral blog memoir to book-length. For the first time in a long time, Valentino felt free. Now, he was doing the only thing he wanted to do: write. The book sold relatively well, landing him a 6-book contract with the biggest publishing house in the Philippines.

His upcoming book is a thriller anthology telling the stories of five different boys in different parts of the Philippines.

Up to the day he died, Kurt never — not once — had a girlfriend. His parents would recall how stubborn he was, ever since he was in the womb. His mother had half a nerve to take him out, citing how impossible and unbearable it was to have carried him. Opposed to what the doctors said that a child that heavy would probably be prematurely birthed, Kurt’s mother had him for 42 weeks. A post-term baby. A latecomer.

Weighing 12 pounds and a little extra with his hands wrapped around the umbilical cord, Kurt was something very special.

That was the way his parents had treated him — with the most special kind of love and care. It was the kind that was coveted by any child: Jollibee birthday parties before he could even remember it, any shoe or toy he would point to, and every single video game under the sun. His family was middle-class at best, but the way Kurt’s parents spoiled him would make you think twice about it.

But Kurt was never happy.

A psychologist told his parents that the action of Kurt wrapping his hand around the umbilical cord was already the first sign of Kurt’s mania. A shaman and fortuneteller would later tell them the same thing. Whether they believed that or not, Kurt’s later lack of motivation would lay the groundwork for the theory. Kurt never wanted to go to school, even having gone to school at a much later time. His pre-school teachers would tell his parents that he had a hard time interacting with both people and objects. He was always observing the room around him with the same shell-shocked face that would carry on even in his teenage years. One teacher suggested that he had an anxiety disorder, always anxious about what the people around him were saying, or doing, or who they were.

Kurt’s parents, in their attempt to raise a normal child, dismissed all these “baseless” theses. Though they knew their son had lifeless stares, tics, and tendencies to not finish things from activities to sentences, they never once treated him like he was any different from anyone.

This, of course, didn’t resonate with the rest of the children.

May it be his anxiety or not, but Kurt was always very observant. He didn’t mind the bullying or the teasing or the name-calling, but he did know they were there. And though, in his childhood, he wouldn’t give a second’s notice to it, everything changed when he discovered what love and lust were. For girls, primarily. In his teenage years, his many attempts to get a girlfriend ended in failure. Everyone knew there was something wrong with him, but no one had the heart to tell him that they didn’t like him because of it So they said it was the way he walked, or his acne, or his hairstyle, or his weight. And just when his parents thought he was changing for the better — taking care of his skin, combing his hair, exercising and molding his physique — no efforts were enough to land him a bride.

What helped Kurt cope was music. Music had never once made him feel different — not in overindulgence or underappreciation. It was always there for him in the push of a button, in the pluck of a guitar string, in a trough of a sound wave. He knew that when he came back home, unaccomplished and unfulfilled, he could sink into his bed as the sound waves snaked into his ears and, in those brief 4-minute flashes, he would be taken to a world where he didn’t need to know what anyone else was saying, or doing, or who they were.

Cole, like most other people, never forgot his first snow. His father was an ambassador for the country, a rather prolific one at that, which required him and his family to move around with only a day’s notice. Among all thirteen countries Cole has made residence in, he never had an experience that beat the snow in Canada. They lived in a more provincial area by choice of his mom. When she heard they were moving to Canada, she requested they live in a mountainous area which was verdant in the summer and glacial in the winter. Cole didn’t know it at 12 years old, but his mother had chosen right. The moment he stepped outside of his house that one chilly morning, he was greeted with an untoppable landscape, pristine and crystallizing. The first snowflake he held in his hand outlined the lines on his palm almost perfectly.

But it wasn’t the day that amazed him. It was the night.

Cole always had an inkling for the dark. His mother would tell him about how behaved he was in the womb. It was almost like he took a masterclass on how to be the perfect baby, she told him. Cole never heard any stories from his father, partly because he shared no interests with him whatsoever, mostly because he was always busy at work. Nightly, he would hear his parents argue through the wall. No matter what country they were in, the fighting never ceased.

This was when Cole began to explore the night around him.

It started with Canada, when it snowed. His parents were fighting unbearably loud. He snuck out his window and examined the world around him. The snow made it seem like the world was moving — in warps, in sharp daggers, in dotted squares. Cole was a creative, ever since he was young, and he would later point this creativity to the natural world. When they moved to Spain the following year, Cole would examine the cracks on the sidewalk, identify the hex codes of the banderitas, and piece out each vein on each red carnation. The nightlife in Metro Manila was his favorite, however. In the times his father had to settle back in the Philippines, Cole would make his way to listen to the rumbles of the busy street, make out the conversations of street vendors and passersby, and time his snaps with the blinking of old and damaged street signs.

The nightlife would become his home when his mother finally caved and left them.

Cole’s father never understood the art that he was making. Stuck to his tradition, he believed men — and he meant men — were to hustle and grind for their money. That art was for sissies and losers. That being creative would never beat being smart. Cole would do everything in his power to avoid conversations like these, sneaking out at night so as to not hear these drunken cautionary tales from his father. And his father never noticed when he left.

At 16 years old, Cole found out through Facebook that his mother, who had once devoted all her time to him, had remarried to a foreigner with three children. The rage he felt was inconsolable. The only person who ever believed in Cole had to believe in someone else — three other someone elses to be exact. He remembered the night after, how he slept under the rain observing the sleekness of each drop on his skin, the seconds between each lightning strike and thunder roar, and the following morning’s petrichor.

That was the night he ran away from home. Leaving his father with only a handful of artworks to remember him by.